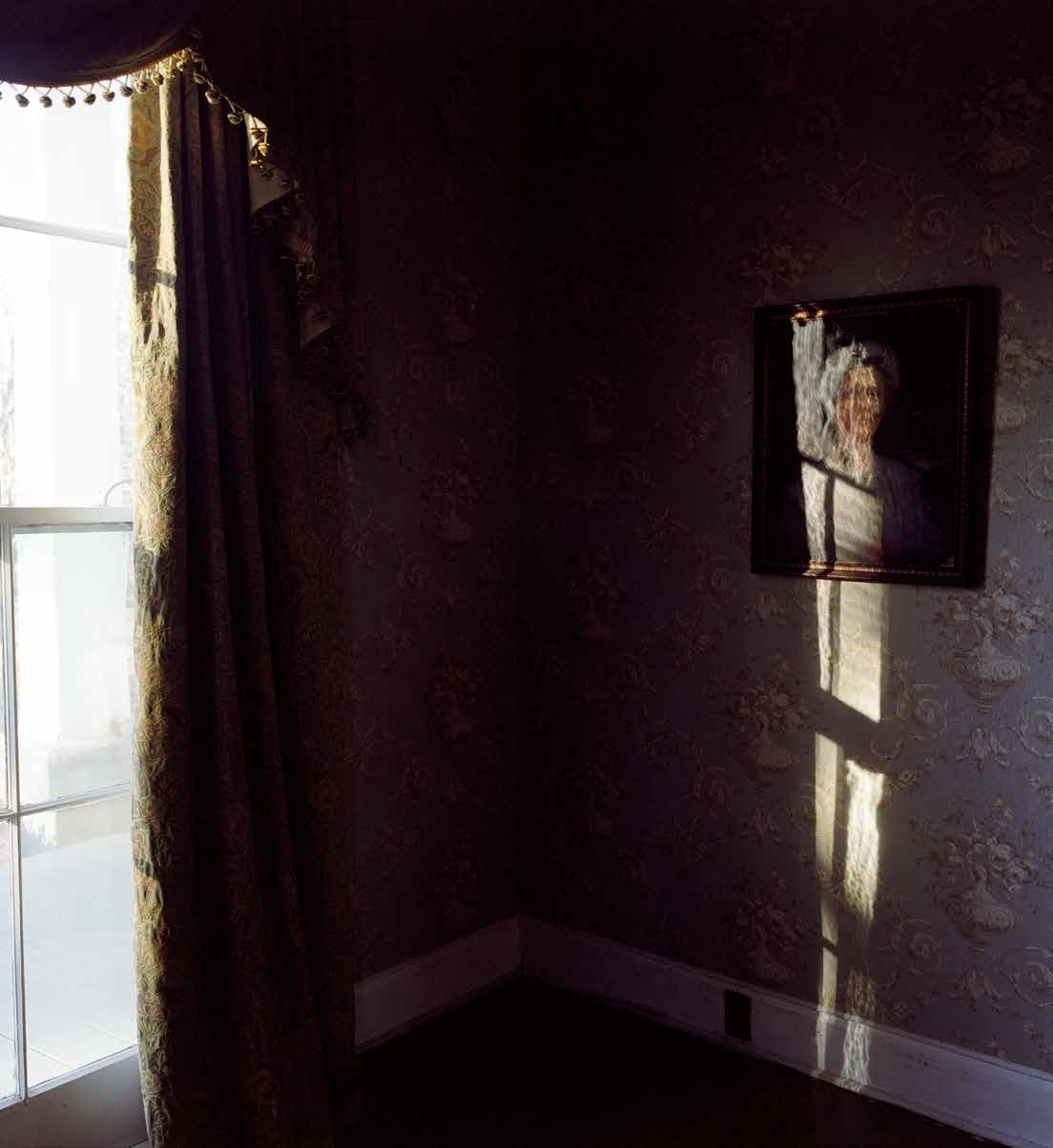

Kathleen Robbins, Cotesworth, 2010. From the In Cotton series. Carroll County, Mississippi

Photography, Poetry, and Truth

Eleanor Heartney

In considering examples that range from the so-called spirit photographs of the nineteenth century, whose doctored negatives purported to “prove” the existence of life after death, to today’s digitally altered Facebook images that place celebrity heads on compromised bodies, one can see that photography’s relationship to truth has always been somewhat tenuous. Documentary photography and its cousin photojournalism, in theory more reliable, have long been the tools of social crusaders and political activists intent on bringing us evidence of the real face of war, the gritty feel of poverty, and the evidence of crime and political malfeasance. Yet despite our desire to believe what we see in photographs, we know in our hearts that complete photographic veracity is an illusion. There is always an element of subjectivity and even deception in the most apparently objective images. A few cases in point: Renowned Civil War photographer Mathew Brady rearranged corpses on the battlefield to create more aesthetic compositions, Robert Capa staged his iconic photograph of a dying Republican soldier in the Spanish Civil War, and Walker Evans added an alarm clock to his photograph of a tenant farmer’s mantelpiece. Even when details are not consciously altered, photographers impose their biases through selection. As Susan Sontag remarked about photographers involved with the Works Progress Administration (WPA) project, they took dozens of images “until satisfied that they had gotten just the right look on film—the precise expression on the subject’s face that supported their own notions about poverty, dignity, and exploitation as well as light, texture, and geometry.”

If this lack of absolute verism is true for historical photographs, it is even truer in the digital era when technological tools make manipulation of photographic images both effortless and seamless. These technical advances coincide with a growing ambivalence toward objectivity, further blurring the line between fact and fiction. We live in a time of “fake news,” “alternative facts,” and “truthiness,” the latter term coined by comedian Stephen Colbert to suggest the condition of something that feels true, even if it actually isn’t. Both academics and ideologues argue that reality is a construct and history a narrative written to advance preexisting political and social agendas. In this climate the traditional aims of documentary photography are increasingly met with suspicion and derision.

Southbound brings together fifty-six photographers who use their medium to probe the complexities of the American South. Only some of the artists here are documentary photographers in the strictest sense, but they all owe a debt to that genre. Many are directly influenced by figures like Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, and Gordon Parks, and a number have actually followed in the tracks of their idols, exploring the same or similar communities, locales, and themes. At the same time, they are keenly aware of the photographer’s role in shaping reality and of the slippery nature of photographic truth in contemporary times. Thus we might ask: What is the proportion of “fact” to subjective vision, political ideology, stereotype, and deliberate deception in the photographs on display? What or whose South do these photographers present?

Alligator Alley, Oregon Road, 2009. From the Road Ends in Water series. Colleton County, South Carolina

Recent controversies over the display of Confederate monuments and symbols reveal the unsettled nature of Southern history. In the images here, one feels a tension between, on one hand, the powerful mythology of the Old South, described by William Faulkner as a “makebelieve region of swords, magnolias, and mockingbirds,” and, on the other, a history that includes still-vivid scars from the Confederacy’s defeat in the Civil War, the legacy of slavery, the persistence of rural poverty, and the scourge of class and racial tensions. The South of today floats between these conflicting visions of past and present. Photographer Mark Steinmetz describes the dilemma: “Most contemporary photographers of the South I think go a bit overboard in making the South seem like an overly gothic, romantic place, though there might be a few photographers who go overboard in the opposite direction by depicting the American South through a ‘new topographic’ prism that makes it seem indistinguishable from, say, the Belgian/German border. I love the South for the weeds growing through the cracks of its sidewalks, for its humidity and for its chaos.”

Steinmetz’s philosophy recalls German filmmaker Werner Herzog’s assertion about the nature of documentary film. In his Minnesota Declaration, he stated: “There are deeper strata of truth in cinema, and there is such a thing as poetic, ecstatic truth. It is mysterious and elusive, and can be reached only through fabrication and imagination and stylization.”

The photographers in Southbound present a variety of strategies for getting at poetic truth. One widely practiced approach might be described as, Engage but also critique clichés. One of the most powerful of these is the trope of agrarian poverty. Photographers funded during the Depression by the WPA program, and later by magazines like Time and Life as part of President Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty, saw themselves as shock troops in the effort to expose the depth of destitution in Appalachia. Although they revealed real problems, in retrospect they also placed an indelible stamp on this region. Shelby Lee Adams, who was born in eastern Kentucky, struggles with this legacy in his own work. He notes that, as an adolescent, he was charged with assisting War on Poverty photographers, and he later felt that he and his community had been exploited. He remarks, “It seemed little consideration was given to the people’s feelings or the deeper life they actually lived and certainly the culture was considered and seen only one way—poor…. That sense of betrayal affected the entire region, not just me. It was an embarrassment to all and still troubles and affects many today.” In his own photographic work, Adams struggles to provide a more rounded picture of the people and culture of Appalachia, creating portraits of individuals that preserve their humanity and dignity.

One sees the same approach taken by many other of the photographers included here. Take, for example, Rob Amberg, who moved to the Appalachian mountains of North Carolina in 1973. He continues to live there on a small farm, sharing the increasingly threatened agrarian lifestyle of the friends and neighbors in his photographs. His images are populated by people who matter-of-factly pursue rural lives that would be unimaginable to their city kin. Similarly, Kevin Kline presents the faces of New Orleans today: students, musicians, laborers, and bartenders who look forthrightly at the camera, challenging the unequal balance of power that gave the WPA photographers their authority.

Lauren Henkin has a less pejorative attitude toward the so-called poverty photographers of the past. In 2015 she retraced the steps of the Great Depression-era photographer Walker Evans in rural Hale County, Alabama. Her work offers not only homage but also reconsideration. While Evans’s photographs present a world literally drained of color, Henkin’s images show the area in Technicolor, endowing both individuals and environments with a sense of vitality and hope. As she notes, “What I was trying to avoid were some of the more stereotypical images of social and economic divide that you see a lot coming from the rural South and really just trying to explore what I found and to leave some ambiguity in the photographs so that the viewers could impart their own narrative.”

As many of the images in this show reveal, the South still contains pockets of deeply rooted rural poverty seemingly untouched by the technological, social, and economic upheavals of the modern world. But that is only part of the story. John Lusk Hathaway chooses to present the clash of contemporary development and agrarian values, as RV travelers, tourists, immigrants, and modern consumers invade the no-longer timeless world of the South. Mark Steinmetz also offers glimpses of both the urban and suburban South, showing a world of highways, suburban sprawl, strip malls, and car culture. By contrast, Lucas Foglia sees strength in the fiercely libertarian streak that underlies certain groups’ resistance to modernity. He seeks out communities of people intentionally seeking to live off the grid. Here, the lack of modern conveniences signals freedom rather than deprivation, and Foglia’s photographs reveal people who seem to live simultaneously in a nostalgic past and a troubled present.

Several artists here remind us that places as well as people can be subject to stereotypes. Michelle Van Parys has explored the old plantations that are such a vital part of Southern mythology and tourism. Yet instead of the more conventional tableaux of rolling lawns, stately homes, and lush gardens, she offers unexpected details and juxtapositions that emphasize a counternarrative of decay, disruption, and dissolution. Thomas Rankin takes on another iconic theme in his exploration of sacred spaces of the South. He photographs African American churches and their adjoining cemeteries and churchyards in the Mississippi Delta, presenting them in black-and-white, devoid of people, emphasizing the hardscrabble emergence of the communities they serve from within an indifferent landscape.

A related strategy embraced by artists in Southbound is, Mix personal history with the complicated political and social history of South. This allows those photographers to accept and acknowledge the inevitable subjectivity of documentary photography. A number of artists in the show use photography to salvage some part of their own past and to explore how it is entwined with Southern history and culture. This is especially the case for artists who left and later returned to their childhood homes.

McNair Evans, for example, grew up in a small farming town in North Carolina but left to explore the wide world. He was called back home by the death of his father in 2000, at which point he discovered that the man he had loved and admired was also a business failure. Seeking to square the man he remembered with this fact, he embarked on a photographic project that involved retracing the places in his father’s life and juxtaposing them with materials from the family archives. The result was Confessions for a Son, a photographic essay that also became an exploration of both the economic struggles of the small farming towns of the Southeast and the sense of both cultural and personal grief that emerges as the remembered past slips away. Evans’s photographs of his family home are suffused with a sense of loss, as simple objects—a pile of magazines, a collection of silverware—become stand-ins for all that has disappeared.

Nashville native Greg Miller has also used photography to recapture his past. When Miller was a child, financial difficulties forced his family to move almost yearly around the city. Returning after an absence of twenty-two years, during which he made a life for himself in New York, Miller found Nashville greatly changed. In order to reconnect with his past, he made a project of revisiting and photographing his various homes and other significant places from his youth. The resulting photographs have an anachronistic quality because Miller deliberately sought out scenarios that reminded him of the 1970s and 1980s of his childhood. There is a sun-drenched sweetness to these images although, as Miller admits, “In the end, if someone is looking at my photographs to find out more about Nashville or even me, I imagine they will be disappointed. To my mind, if these pictures succeed, it is because so many make a similar journey back home.”

Kathleen Robbins tells a similar story. Her grandfather was a third-generation cotton farmer in the Mississippi Delta, and she grew up on her family’s farm. She now lives in Columbia, South Carolina. When she visited home as an adult, she discovered that cotton was disappearing and the life she remembered no longer existed. The camera became her way to retrieve her memories of a lost world. Like Miller, Robbins employs a kind of time travel through photography, making images of lonely farmhouses, empty fields, and dilapidated structures that are a poignant mix of past and present.

Will Jacks presents a more joyful present-day paean to the past. A native of Cleveland, Mississippi, Jacks has copiously documented the juke joint Po’ Monkey’s Lounge outside of Merigold, Mississippi. Until the death of its owner, Willie Seaberry, a.k.a. Po’ Monkey, in June of 2016, this modest shack was a second home to musicians and music lovers throughout the region. Jacks recounts how frequenting Po’ Monkey’s helped him reconnect with old friends and classmates and gave him a sense of community. His photographs reflect what he has described as the “unconditional love” he felt there; they depict denizens merrily drinking, laughing, dancing, and socializing under the benevolently watchful eye of the establishment’s owner and patriarch.

Nashville native Bill Steber has a similar story to tell in his photographic history of the Mississippi blues culture. For twenty years he has documented the vibrant world of blues musicians, juke joints, hard drinkers, and Saturday night revelers. As he points out, these are not the famous bluesmen who left the Delta region to achieve fame elsewhere; rather, they are the day laborers, farm hands, and itinerant workers for whom music is a solace and an escape from the difficulties of daily life. A musician himself, Steber sees this project as a mission, noting, “I was racing against time to photograph these places (generally disintegrating juke joints and shotgun sharecroppers’ shacks) and these people before they all were gone.”

While some artists intentionally put themselves in the story, Keith Calhoun and Chandra McCormick found themselves implicated involuntarily. Long-time residents of New Orleans, the pair is known for photographs of life in the African American communities in the Lower Ninth Ward in New Orleans and rural Louisiana. They fled the city during the onslaught of Hurricane Katrina in 2005, only to return to find their home destroyed and boxes of negatives irreversibly water damaged. Rather than throw them out, they developed them and discovered that the ravages of the storm had transformed the images in unexpected and often beautiful ways. The photographs from this series, with the images partially or completely obliterated by cracks, mottling, and discolorations, become a metaphor for the disruption of lives by the monumental storm.

A third approach to the documentary tradition in evidence here is the adoption of the role of the roving photographer. It might be summed up as, Expand your horizons through the lens of a camera. Interestingly, many of the roving artists in this show are foreign born and bring an outsider’s perspective to their examination of aspects of Southern life.

In this category are photographers like Madrid-born Daniel Beltrá, who has traveled the seven continents to document environmental catastrophes and endangered landscapes. For Southbound he contributes aerial photographs of the effects of the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico; his images are both alarming and disconcertingly beautiful. Lima-born Susana Raab takes a closer view with her exploration of the American character as seen through small-town fairs, theme parks, conventions, and rituals. Raab’s images represent the artist’s desire, in her words, to “show a part of the fullness of our experience and hope that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.”

Magdalena Solé was born in Spain during the years of Francisco Franco’s dictatorship; as a child, she and her family were exiled to Switzerland. She connects this experience with her interest in outsiders and people living at the margins of society. She brings this perspective to her series Forgotten Places, which includes her explorations of the people and places of the Mississippi Delta. She notes, “The Delta is one of the poorest places in the United States with the saddest infant mortality rate, rampant unemployment and little hope for a better future. What is little known is the resilience, resourcefulness and family cohesiveness of its people.”

Meanwhile, Hong Kong-based Kyle Ford focuses on the tourism industry, bringing to life a world in which everyone is an outsider. In the images included here from his series Second Nature, he examines the way in which tourist attractions have domesticated, replicated, and otherwise reinvented the experience of nature, offering such enticements as sea animals frolicking in an aquarium and fake mountains on a carnival ride.

Whereas Ford’s photographs playfully mock our attempts to manufacture nature, other artists offer a more serious take on the reinvention of reality. The principle here might be stated as, Embrace fabrications that may lead to deeper truths. They deal in what we might designate faux history, either through adoption of old and antiquated photographic techniques or by seeking out situations in which history is replayed by contemporary actors.

Outmoded photographic processes can seem to turn the present into the past. Lisa Elmaleh creates tintypes of musicians who play traditional American folk music in Appalachia. Tintypes, which are made by creating a direct positive image on a thin sheet of metal coated with a dark lacquer or enamel, were the favored medium of itinerant photographers in the nineteenth century. Elmaleh’s portraits evoke the formal poses and artificial backdrops of those earlier images, literally placing her subjects back into the history from which they have emerged.

Euphus Ruth employs collodion wetplate photography using vintage cameras and lenses. Related to the tintype, this process was also popular with nineteenth-century photographers. In Ruth’s hands, it seems to transport subjects like river baptisms, old cemeteries, and Delta landscapes into the past, serving as an elegy for places, customs, and structures that are being erased in the name of progress.

Civil War reenactments provide another sort of elision between past and present. Several artists in Southbound provide glimpses of the fascinating subculture that has grown up around these often very elaborate role-playing dramas. Anderson Scott’s series titled Confederates follows Civil War reenactors in Georgia, Alabama, South Carolina, and Florida. He presents them not in full regalia at the height of battle, but in moments of repose or preparation when anachronistic details mar the illusion. He is interested in the clash between such historical role-play and the conveniences and realities of the modern world, noting “the incongruity that cropped up again and again of people trying to be historical in the current world.”

Thomas Daniel, by contrast, strives for an appearance of authenticity in his documentation of Civil War reenactments. Himself a Vietnam veteran, Daniel uses black-and-white film and dramatic lighting to present the soldiers and their battles as a documentary photographer in possession of today’s technology might have captured them. Although the action photographs he creates were beyond the medium’s capacity in the mid-nineteenth century, his images of battlefields strewn with bodies are deliberately evocative of the work of Civil War photographer Mathew Brady.

Eliot Dudik takes yet another approach. He has created portraits of reenactors in costume as they lie on the ground, seemingly both dead and alive simultaneously. He has also, in the series represented here, returned to famous battlegrounds and photographed them as they are today. Even when not populated by reenactors reliving the battles, these landscapes are haunted by the death and destruction that overtook them one hundred fifty years ago. Dudik ascribes a political lesson to these photographs, noting, “These photographs are an attempt to preserve American history, not to relish it, but recognize its cyclical nature and to derail that seemingly inevitable tendency for repetition.”

Equally immersed in a difficult past, Jeanine Michna-Bales uses photography to re-create a history for which almost no images exist. Her subject is the Underground Railroad, the crisscrossing paths and havens that runaway slaves used in their bid for freedom. Having exhaustively researched this highly secret network, she has created a haunting sequence of photographs that suggest the route an individual slave could have taken to freedom, through the landscapes of Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Tennessee, Indiana, Michigan, and, finally, Sarnia, Ontario. The scenes in the South are all nocturnal, reflecting the reality that slaves could only move safely at night. Through photographic fiction, viewers are provided a sense of the fearsome reality that faced the runaway slave.

Chris Sims, meanwhile, reveals how enactments serve a very contemporary military purpose. In a series titled Theater of War, he photographs the fake villages set up as training grounds by the U.S. military in the forests of North Carolina and Louisiana. The villages provide soldiers preparing to be shipped off with scenarios and environments very like those they may expect to find in the real battle zones of Iraq and Afghanistan. Sims enters these villages both as an authorized visitor and as a player enacting the role of a war photographer. Ironically, many of the “villagers” the soldiers interact with are themselves recent immigrants from those embattled countries who now re-create moments in the lives they left behind.

And finally, Southbound presents a number of artists who share the reforming zeal of the pioneering documentary photographers of the WPA. The principle they ascribe to might be formulated as, Pursue a political/social agenda in the spirit of the WPA photographers, but update and complicate the problems you present.

Thus, for instance, Georgia native Sheila Pree Bright employs photography in her fight for racial progress in America. She draws a line between the often violent clashes of the 1960s civil rights struggles and today’s Black Lives Matter movement. Her black-and-white photographs of the latter are deliberately reminiscent of news photographs from the earlier era, underscoring the continued survival of such problems as police brutality and the mass incarceration of black men.

Tennessee native Jessica Ingram is also immersed in the history of civil rights. She approaches the subject in a very different way, documenting the now seemingly innocuous sites where atrocities like lynchings, Ku Klux Klan rallies, and slave trading took place. She thus describes her mission as “a meditation and a recapturing, a new memorial to these events—some of which have been excluded from the collective and mediated retelling of this period in our history.”

Although an outsider to the region (she hails from New York), Gillian Laub found herself drawn into a contemporary story about the persistence of racial injustice. Sent by Spin magazine to the small Georgia town of Mount Vernon for a story on segregated proms, she ended up working there for twelve years, getting to know the community and its tensions. During this time she observed how the local high school homecoming events eventually became integrated while the prom remained segregated. Meanwhile, she also began to follow related stories, among them the killing of a young unarmed black man by an older white man and an apparently fraudulent local election that snatched victory from a black candidate for mayor. The fruits of her labor include an HBO documentary as well as a series of photographs of the segregated prom, whose publication in the New York Times finally brought about integration of the prom. Photographs from that event appear in this exhibition and catalogue.

Other marginalized groups have also been given voice by Southbound artists. When Arkansas native Deborah Luster was thirty-seven, her mother was murdered by a hired killer. In a remarkable act of compassion, Luster has come to terms with that wrenching memory by photographing inmates in Louisiana state prisons who have been convicted of violent crimes. Instead of reducing them to the worst acts of their lives, she presents them as they would like to be seen, allowing them to pose themselves and choose their props and contexts. The works included here present inmates dressed in homemade costumes for their roles in the prison’s Passion play in 2012 and 2013.

Sofia Valiente photographs a group of ex-convicts who have left prison but still find themselves trapped by their past. Her subjects are the inhabitants of a Florida community called Miracle Village, which was founded by a Christian ministry to provide homes for sex offenders. Living in the village are men (and one woman) who have essentially been shunned by society and, due to Florida’s strict residency restrictions, have no other place to live. Like Luster, Valiente restores humanity to a population that tends to be demonized, giving visibility to their comraderie, loneliness, and social isolation.

Other Southbound artists explore the toll exacted on traditional mores, communities, and landscapes by development and modernization. Although their investigations are grounded in the South, the work they do points to problems evident in the larger society as well. For example, Tennessee-based artist Rachel Boillot has made a photographic study of the disappearance of rural post offices. Lauded as a cost-cutting measure, this development threatens to impoverish even further communities that are already overlooked. Her photographs document this endangered species as well as various marginalized groups, among them migrant workers and American roots musicians.

Mitch Epstein examines the impact of America’s insatiable thirst for energy in his series American Power. His photographs take on all aspects of energy production and consumption, personalizing it with images of the users and producers as well as scenes of environmental impact and community disruption. The series is meant to challenge the American belief that growth always represents progress. A similar motivation lies behind Daniel Kariko’s documentation of the impact of real estate foreclosures in Florida. His desolate aerial photographs of abandoned developments chronicle the end result of a cycle of boom and bust that followed from unfettered expansion. Jeff Rich, meanwhile, focuses on water issues ranging from recreation and sustainability to exploitation and abuse. In his photographs we see the remaking of lives and landscapes under the sway of the Tennessee Valley Authority, the institution that regulates all aspects of water management in the Tennessee Valley. By focusing on individuals, community groups, and specific landscapes, Rich humanizes the operations and impacts of this massive public works project.

The American South is a subject rich in contradiction and fraught with tension. Tamara Reynolds could be speaking for many of the photographers represented here when she says, “I cringe at how the country has stereotyped the South as hillbilly, religious fanatic, and racist. Although there is evidence of it, I have also learned that there is a restrained dignity, a generous affection, a trusting nature, and a loyalty to family that Southerners possess intrinsically. We are a singular place, rich in culture, strong through adversity. We are a people that have persevered under the judgment of the rest of the world. Ridiculed, we trudge carrying the sins of the country seemingly alone.”

In On Photography, her classic meditation on the medium, Susan Sontag says, “To collect photographs is to collect the world.” This exhibition is part of that effort. There are so many faces here—young, old, white, black, Hispanic, grizzled, clean, careworn, pampered. So many landscapes—pitted country roads, threadbare main streets, expansive cotton fields, urban throughfares, mysterious bayous, sun-dappled swimming holes, manicured suburban lawns, disrupted waterways. So many reminders of history and markers of mortality—Confederate flags, historic churches, magnificent plantation houses, derelict trailers, dilapidated shacks. Revealed here is the dark side of the human soul, but also flashes of hope and happiness bursting through in musical celebrations, joyful communal rituals, and dusky skies darkened with flocks of birds. Represented in these photographs are personal visions and public spectacles, histories that were and histories that might have been. Together they create a mosaic that approaches reality, a South that is multifarious, and a truth that is manifold.