In Lil Wayne’s dirge and several of the songs on this list, a robust sense of place and various manifestations of community pride, albeit seldom without some sense of internal conflict, are present. This can be heard in Mississippi hill-country bluesman Cedric Burnside’s reminiscing on “Front Porch,” New Orleans soul singer Brother Tyrone’s retrospective paean to his native Sixth Ward in “New Indian Blues,” Atlanta hip-hop artist Cool Breeze’s localized anthem “WeEastPointin’,” and Mississippi soul singer Jaye Hammer’s comically defiant “I Ain’t Leaving Mississippi.”

Solo, non-vocal tunes—what musicologist Richard K. Spottswood calls “display pieces” and we know as instrumentals—continue to stand as a major element in many arenas of southern musicianship, as indicated, for instance, by increased attendance at the region’s many fiddlers’ conventions. The late Etta Baker (1913–2011) of Morganton, North Carolina, was certainly one of the Southeast’s finest guitarists and an unrivaled twenty-first-century matriarch of the Piedmont school of fingerpicking; here she is heard playing an uncommon banjo tune, “Peace Behind the Bridge,” accompanied by her friend folklorist Wayne Martin on the fiddle. Harpist Mary Lattimore of Asheville, North Carolina, summons otherworldly vitality and refreshing innovation from an ancient instrument on “Hello from the Edge of the Earth,” as does young guitarist and folk-music researcher Daniel Bachman of Fredericksburg, Virginia, on “Song for the Setting Sun I.” The opening track on this list is a fragment of a tune played on the khene, a type of mouth organ constructed of bamboo reeds that is native to Laos, and was brought to Alabama’s Mobile Bay by Reagan Ngamvilay, one of thousands of Southeast Asian refugees who fled to the U.S. Gulf Coast in the 1970s and 1980s to escape political and social turmoil resulting from the Vietnam War and surrounding conflicts in Laos and Cambodia.

As in the corrido tradition and in the wealth of political and protest songs that arose from the abolition, labor, and civil rights movements in the South, a number of the songs here challenge and express discontent with various power structures, systems of hierarchy, and the numerous social inequities—explicit and implicit, personal and institutional—that continue to dominate life in the region and beyond. These themes are most directly illuminated in “Living Hell,” by the feminist post-punk band Fitness Womxn based in Carrboro, North Carolina, and “At the Purchaser’s Option,” from songwriter Rhiannon Giddens of Greensboro, North Carolina, which conjures the horrors of an antebellum past and brings them into sharp focus in the present tense.

All too frequently, anthologies and histories of southern music marginalize American Indians as nothing more than an historical footnote. Listeners here will find several examples of southeastern Native American music ways, including a Cherokee-language version of the spiritual standard “Guide Me, Jehovah,” performed by the late banjo player and medicine man Walker Calhoun (1918–2012), “At the Cross,” a spiritual by Cherokee husband-and-wife gospel duo Nancy and Mark Brown, and a recent field recording of a Lumbee Indian congregation singing at the Union Chapel Community Baptist Church in Pembroke, North Carolina. Religious and ceremonial music, including these types of Christian gospel hymnody, have continued to prove as culturally relevant as any other form of creative expression in the region.

While some folklorists and musicologists have worked on the presumption that they were documenting traditions at risk of imminent extinction, others have foreseen revivals of interest in seemingly endangered genres, and ethnomusicologist Alan Lomax, who was prone to romantic generalizations on occasion, couldn’t have been more spot-on when, in the early 1980s, he predicted that the Sacred Harp school of shape-note singing would experience an enthusiastic rejuvenation led by young singers across the nation and elsewhere. The Sacred Harp legacy is now going as strong as ever, and one can get a sense of its resilience in the passionate singing heard at the Henagar-Union Sacred Harp Convention in northeastern Alabama, where pieces like Isaac Watts’s early-eighteenth-century hymn “Ninety-Fifth,” alternately known as “When I Can Read My Title Clear,” are performed alongside contemporary compositions.

Gospel music aside, individual visionary experiences and various spiritual ruminations continually inform the music of southern composers and performers. Some of these reflections and revelations are illuminated here in the magical realism of New Orleans poet-rapper Jay Electronica’s “Voodoo Man,” the search for salvation by Florida-born Mississippi songwriter Tyler Keith and his band The Preacher’s Kids on “Crooked Road,” the cosmic biblical musings of late South Carolina artist and singer Charlie McAlister (1969–2018) in “Darla Come Down from Jackson,” and in the Alabama visionary artist Lonnie Holley’s lifelong quest for “All Rendered Truth.”

Universal themes of earthly desires and the search for love, companionship, and understanding, often situated in the realm of the natural world, are evident in many of these performances, perhaps most of all in Memphis rock band Reigning Sounds’ “Not Far Away,” Natchez-born songwriter Olu Dara’s “Tree Blues,”Louisiana native Lucinda Williams’s “Fruits of My Labor,” and in experimental musician and composer Matana Roberts’s haunting and ominous “Woman Red Racked,” which was informed by the field recordings of Alabama singer Vera Ward Hall.

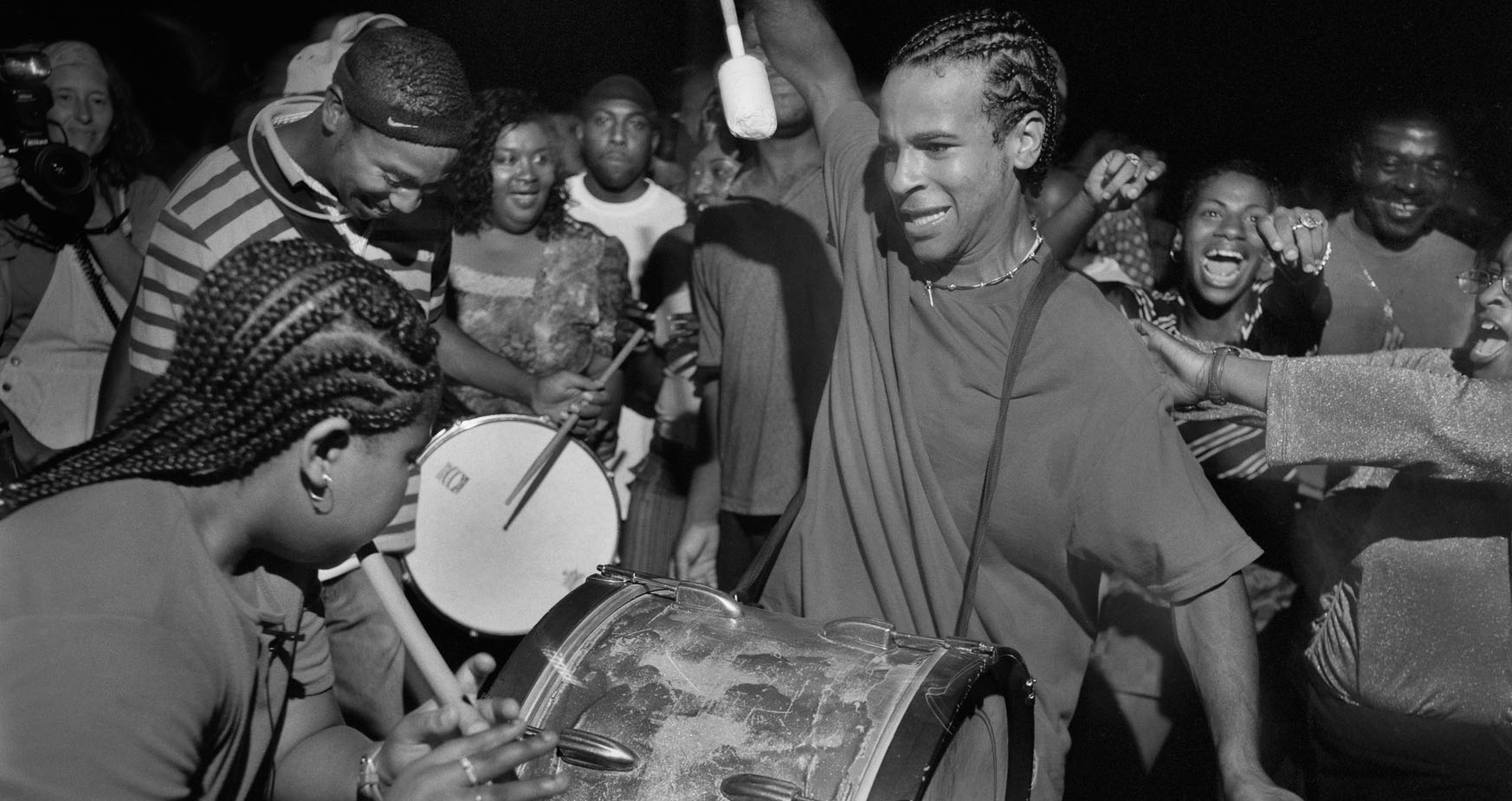

Other performances here will inspire the listener to dance, chief among them “Bonsoir Moreau,” a longtime favorite waltz in the dance halls of south Louisiana, played here by Les Amis Creole, the infectious and intoxicating “Gin in My System” by reigning Queen of Bounce Big Freedia, and “Put Your Right Foot Forward” by New Orleans’ all-woman second-line group The Original Pinettes Brass Band.

It is fitting to conclude this playlist with such a performance, not only as an example of the central role that dance has played in the development and continuation of the South’s many musical cultures, but also because the song calls its listeners to come forward and to participate: “Put your right foot forward, drag your left to the rear / Put your right foot forward, and bring your hands right here.” This ongoing, ecstatic interplay between the movement of the individual and the shared, collective experience may well serve as an appropriate framework for listening to and thinking about the music of the New South, as southern musicians continue to respond to the realities of the present by reshaping and challenging longstanding community traditions through participation and resistance.