Curating the Map

Geographers, whose discipline is perhaps most closely associated with maps as tools to communicate ideas about the world, are the first to recognize the limitations of those maps. For all the power that we vest in them, maps suffer the shortcomings of the cartographer’s competence, intent, and perspective, and they are dated even before they go to press. Like all representations, their meaning is not necessarily self-evident, labels and keys notwithstanding, and, ultimately, cannot be disentangled from their contexts. No one would argue that maps made by colonial surveyors or indigenous shamans are one and the same, nor that they meant the same things to viewers when they were made as when revisited decades or centuries later. Introductory college-geography courses glory in confronting students with map projections that underline how outlandishly enormous Alaska is on the time-honored Mercator map (however ideal it is for navigation); in showcasing the purported “upside-down” map of the world with the Southern Hemisphere at the top of the globe; or in using Pacific-centered maps to confront the ethnocentrism of a world anchored by the Atlantic Ocean, emblazoned into our consciousness by European cartographers from the sixteenth century onward.

Maps then, like photographs, for all the authority we confer on them, present us with imperfect renditions of places. So it must be, too, with Southbound’s map of the South, which could be more accurately called an index of Southerness in that its maps track historical, economic, religious, demographic, commercial, and cultural indicators. It affords us a more traditional cartography with which to parallel the images of the South that congeal through encounters with the Southbound photographs. Just as with those images, viewers have some latitude in configuring their experience through selection of the markers they prize most in defining the region. That is achieved through successively switching layers on and off in a digital mapping environment, available to viewers of Southbound in the exhibition space or on the project webite. The multiplicity of maps of the region available there can be overlaid to create our Index of Southerness, in which indicators intrinsic to the region, like religion, race, or the memorialization of one people’s vision of history there, can be weighted to reflect that fact.

The Index incorporates multiple maps that are generated from the querying of many databases, from the census to commercial datasets to datasets of school and street names countrywide. Some of the maps seem to transpose markers such as census counts of race more or less directly to the Index, yet they are heavily processed; thus, our map of race measures the clustering of populations by county, suggestive of longer term patterns of habitation rather than a mere snapshot of distribution. The maps that make up the Index required extensive processing to discover places all the way across the United States where, for example, Confederate generals are memorialized in the landscape in street, school, and library names; the same can be seen in the names of civil rights activists or synonyms for the region like magnolia or Dixie. The cleaned-up street-name dataset alone contains almost nine million records and was queried using more than six hundred search terms. The resulting map of counties countrywide, of variables from street and business names to Civil War monuments to magazine subscribers to students’ vernacular maps, all make the region we call the South clearly visible.

Geographers understand that regions are dynamic, always in flux, always emergent. They also recognize, however, that there are places where the aggregate of regional culture resonates most fully, a core, where, in this case Southerness, however defined, endures. One vernacular region that might equate to the Index’s core is the so-called Deep South. This is a place associated with particular histories, a multiplicity of accents all patently Southern, a constellation of foods and drinks that, as we learn and relearn, all taste of the South, where rural ways of living reigned longer, among many other indicators. Around that core is found a domain where maps underline the dominance of the cultural attributes under consideration, even as their intensity declines. Distance decay accounts for further decline across space so that such cultural markers are less prevalent but still present in the larger sphere.

Our mapping of the South showcases just such patterns of core, domain, and sphere. Further, mapping at the county scale calls into question the all-too-convenient cartography of the South following state lines. If history were all that mattered in defining the region, then state boundaries might make sense, but if we understand the South as multifaceted, then indicators such as religion, historical markers, and business names transition across space.

The Index maps also show other parts of the United States where indicators associated with the region are to be found. The magnolia, for many a quintessentially Southern tree, can be mapped readily in street and cemetery names all through the South, for example, but there are many places outside the region where it is also to be found, southern California for one. The construction of the Dixie Highway network, running north–south to connect the South and the Midwest, just when monuments to Confederate heroes were inscribing a menacing vision of history into the Southern landscape, serves today to pull places in Illinois, Ohio, and Indiana partly into our digital map of the region. The term Dixie, moreover, would have caught the eye every bit as much in the Midwest as it did in the erstwhile Confederate states, more so for African Americans.

Mapping the entirety of the country at the county scale creates a rich tapestry of markers all across the United States. It underlines commonalities throughout the territory but serves, too, to highlight the South. Viewers of Southbound can use the Index of Southerness to puzzle over their own visions of the region by combining indicators from the demographic to the commercial to the historical, to take several examples. As is the case in viewing the exhibition, catalogue, and website photographs of and about the region—the Index provides a platform from which to reengage with this place.

Emplacing the New South

Each component of this project’s title—Southbound: Photographs of and about the New South—lends itself to scrutiny. Southbound refers to the twin ideas of heading south and the lingering effects of charged stereotypes that limit our ability to see the region clearly. Photographs refers to documentary and fine art images but, in this case, does not include constructed or fabricated photographs. New and, particularly, South are perhaps the most slippery elements of the title. South because, like all regions, it is necessarily a function of how we define the parameters—climatological, historical, cultural, and so on. New for the many instances that adjective has qualified developments in the South, often purportedly definitive in terms of change, and always to create distance from lesser and sometimes unsavory moments in the region’s history. Indeed, we considered calling the exhibition New South2, then cubed, and might have settled on New Southn, if it weren’t too cryptic to be clever.

Successive generations of Southerners have laid claim to theirs as a region in transformation, new for the constellation of social and economic changes reconfiguring life there, ever since the term New South was coined in the decades after the Civil War by an Atlanta newspaper editor to promote the transition from plantation agriculture to industrial economy. The year 2000, benchmark for the selection of photographs for inclusion in Southbound, presents a tantalizing proposition in reaching, again, for the idea of a New South as we swing into a new century and millennium. Yet there are processes of change, some long since underway in parts of the region and, now, increasingly in evidence region-wide, that together recommend this as a newest New South.

If the South is indeed being transformed in the early twenty-first century, then demographic changes like the influx of Latin Americans throughout the region are part and parcel of that process. So, too, are the ongoing reversal of the Great Migration and the decision of retirees from northeastern and midwestern states to relocate here. All of these new Southerners enrich the cultural map of the region, contesting received truths about the South. Many of them take residence in boomtowns along the coast, and some move to cities undergoing wholesale urban renewal as people rediscover downtowns as places to live. This changing urban map is underpinned in part by massive infusions of both international and domestic industrial and financial capital. All of this is taking place, moreover, in a region being remade by the digital revolution. The amalgam of demographic, urban, economic, technological, and concomitant social changes makes for a vibrant New South.

Modernization entails an array of transformative forces like these being unleashed upon a place. In that sense it is synonymous with Americanization worldwide, and while the outcome of processes of change is always syncretic and cuts both ways, the net effect is one of making places more similar over time. Partly for that reason, people often look to traditional identities as anchors in a changing world, and, in that light, perhaps, photographers working in the region may be drawn to local distinctiveness over homogeneity. Similarly, many of our decisions around what to include in Southbound foreground the particularity of this place.

To experience the South on the ground as we researched the project, both in the field and remotely through the Southbound photographs and the Index of Southerness maps, was to encounter the resilience of the region. The Southbound photographers stress a connection to place at scales that range from the regional to the local to the micro-geography of a juke joint in the Mississippi Delta. That connection speaks to our absolute dependence on the organic world, with all its connotations of traditional ways of being, something underplayed by many in our headlong rush to be on to the next brightest thing, and, for some, secondary to our looming digital existence. Senses of place in the South crystalize in the spaces between today’s emerging New South and echoes of Souths past.

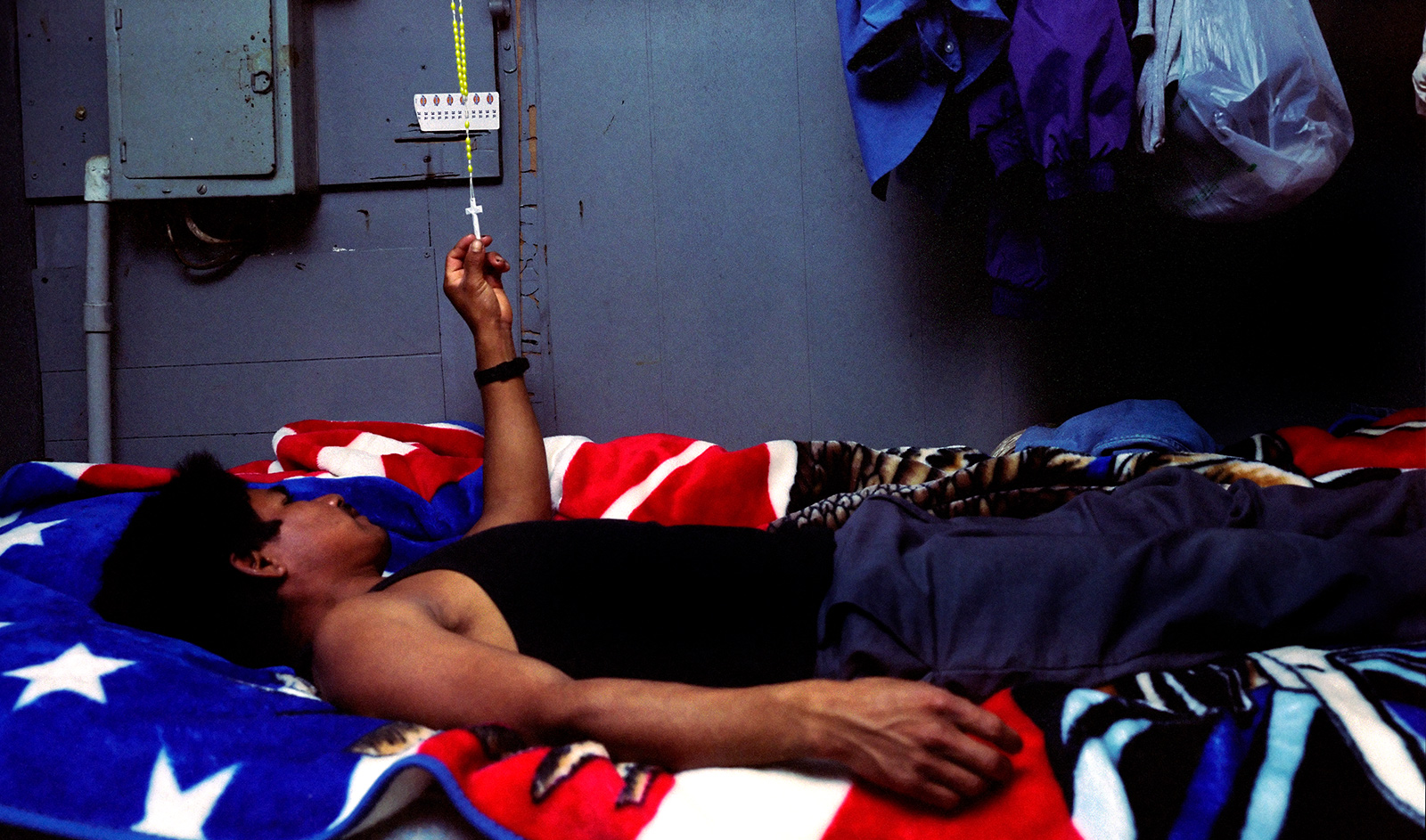

Today’s South, then, can be intuited in the tensions between celebration of the past as seen in the work of photographers such as Thomas Daniel, gone native with a band of Civil War reenactors, and trepidation that we should repeat the mistakes of that past as explored by Eliot Dudik in his revisiting of Civil War battlefields, or in Gillian Laub’s photographs of segregated proms that bear witness to disturbing holdovers from the region’s history. It is manifest in cycles of boom and bust for industries from tourism to construction, as reflected in the photographs of Kyle Ford and Daniel Kariko. It can be found in the urban experience in Atlanta and Nashville, photographed by Mark Steinmetz and Greg Miller, respectively, that rural dwellers in Madison County, North Carolina, and in intentional communities across the region recoil from, as pictured by Rob Amberg and Lucas Foglia in their projects. The region is plain to see in photographs of longstanding communities in Shelby Adams’s Kentucky, Eugene Richards’s Arkansas, and Brandon Thibodeaux’s Mississippi, yet it is also evident in images of new arrivals to Susana Raab’s Florida and Rachel Boillot’s North Carolina.

Michelle Van Parys’s photograph Overpass with Flag (2015), from her Beyond the Plantation series, encapsulates the conundrum of the region. Layered into the image are a live oak tree and Spanish moss, water and marsh, high tension cables, an interstate highway overpass, and an industrial plant above which flies the Stars and Stripes, all inviting us to peer through our preconceived notions about this place to see a New South. The contradictions inherent in the region are also on display in Alex Harris’s Grand Marshals Ball, Battle House Hotel (2010), from his Where We Live series, which shows a group of elegantly attired African Americans celebrating in a grand ballroom. The ballroom is decorated with a tapestry depicting log cabin colonials, one of whom is reading from a parchment that, for the ship moored over his shoulder, might be a manifest detailing the most nefarious of all cargoes transported to these shores. Even though so much of the South’s history is bracketed by those groups, the easy and joyous leisure of the revelers suggests that much has changed.

In his photograph Garden Party (2012), from his The Invisible Yoke, Vol. III: The Seven Cities series, Matt Eich’s juxtaposition of a portable air-conditioning unit—synonymous with the economic rebirth of the South during the decades after World War II—with bejeweled ladies in period dress conversing at the Virginia shore, also speaks to long trajectories of change within the region. Near the women are plywood cutouts of a dog and cat, and, in the distance, quayside ship-to-shore gantry cranes line the waterway at one of Norfolk’s container ports. Future changes, too, are alluded to in Keith Calhoun and Chandra McCormick’s scenes from the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans and in Stacy Kranitz’s portraits from America’s first climate-refugee community on Isle de Jean Charles in Louisiana. Bellwethers of the environmental challenges facing the South and elsewhere, these images charge the region with foreboding.

The New South is revealed in Jessica Ingram’s Stone Mountain Confederate Memorial Carving, Stone Mountain, Georgia (2006), from her Road through Midnight: A Civil Rights Memorial series. The photograph shows an African American woman in an aerial tram car, swinging up to the top of a colossal granite monolith that features what is ostensibly the world’s largest high-relief sculpture, brainchild in part of the same sculptor who created Mount Rushmore, Gutzon Borglum. As that African American day-tripper trains her camera on the Confederate generals carved into the mountainside at the site of the rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan a century ago—and now given over to tourism, hiking, and shopping—the momentary dissonance recreates the vertigo of Stone Mountain’s Summit Skyride and we fall headlong into the complicated place that is the New South.

The tension between stasis and change defines today’s New South, as it will future New Souths in turn. Southbound holds a mirror up to friction along the seams of ongoing transformation in the region—halting, heady, and traumatic as it may be—revealing of the places the South was, is, and will in all likelihood become.